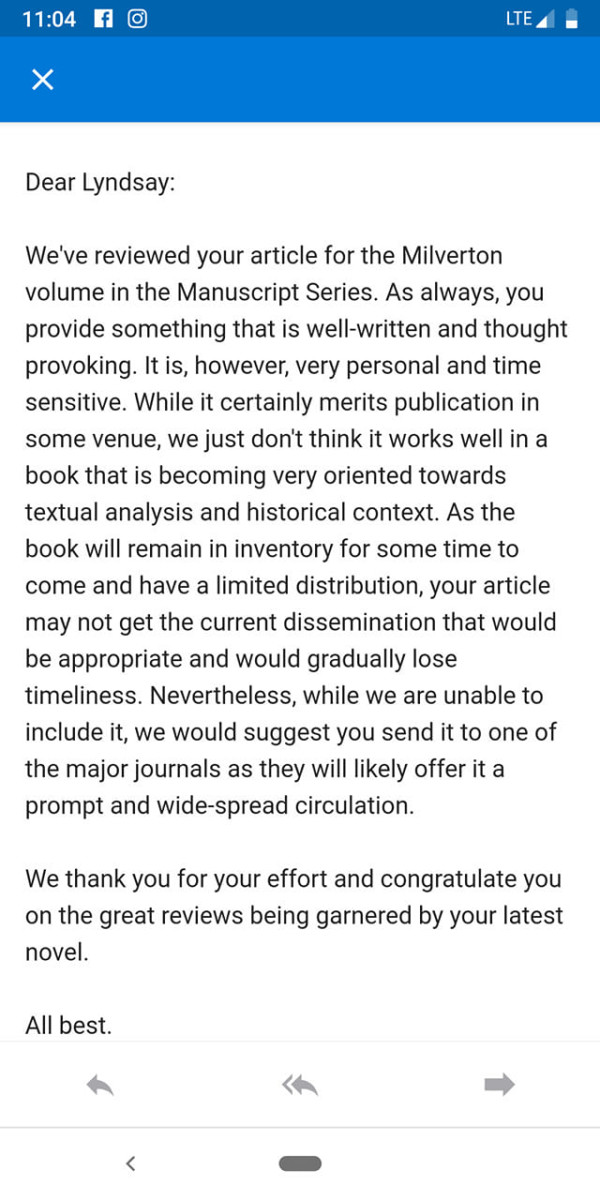

Is It Discreet? Is It Right? “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton” in the Post-#MeToo Era

The following article, written by Lyndsay Faye for a BSI manuscript series, was rejected. Why? For being too “timely.” Feminism is not a fad. #MeToo will not fade away just because it makes men uncomfortable. Looking at a story through a female lens isn’t “evergreen” apparently.

Bullshit.

We’re disgusted, furious, offended, but sadly… not surprised. The BSI as a whole has come far, but apparently there are still ancient pockets filled with dinosaurs and men afraid that if they let the ladies speak their minds just a little too much, people won’t be able to handle it.

So we’re posting Lyndsay’s essay here, because we believe feminism won’t “gradually lose timeliness.”

Is It Discreet? Is It Right?

“The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton”

in the Post-#MeToo Era

Few villains in the Sherlock Holmes Canon inspire heartier revulsion than Charles Augustus Milverton—not merely on the part of the reader of Dr. John Watson’s accounts, but that of the Great Detective himself. To provide a bit of contrast: when Holmes speaks of Professor James Moriarty, his tone is often one of reluctant admiration, if not downright regret over his arch-rival’s otherwise unlamented demise. While Watson chides his friend that few of the law-abiding citizens of London would agree a criminal mastermind should be missed overmuch, he also comprehends that Holmes’s intellectual needs are voracious, insatiable, but never malicious. Despite his legendary ego, Holmes can’t be expected to solve every crime in London; and barring that possibility, he devotes himself single-mindedly to solving only the most grotesque and challenging conundrums. Moriarty’s combination of brilliance and amorality provided Holmes with as much of a service as he did a problem, no matter how much Watson might rue admitting it.

Not so with Milverton. When one contrasts this attitude of nostalgia for the good old days against Holmes’s utterly repulsed demeanor towards the Master Blackmailer, one quickly sees how deeply our hero despises the criminal he characterizes as the worst man in London. And when he explains that there can be no comparison between “the ruffian, who in hot blood bludgeons his mate, with this man, who methodically and at his leisure tortures the soul,” it is difficult to summon any counter-argument. Considering the facts that Milverton preys on women guilty of mere possession of a sex drive—or still worse, an open and trusting nature—and that his entire livelihood is based on ruining them, the urgency Holmes feels over his destruction becomes not only understandable, but chivalrous and in large degree unselfish. Remember that Holmes’s appetite for mental exaltation plays no part in this particular case. As a negotiator given no opportunity to negotiate, he is merely a hired intermediary on the part of Lady Eva Blackwell—a minor role at which he would normally scoff.

The hashtag and phrase #MeToo (or often Me Too, when found in print media) is now widely associated with the downfall of accused serial sexual predator Harvey Weinstein after a series of exposes by Ronan Farrow were published in The New Yorker. But “Me Too” as a movement was actually founded by Bronx-born African American civil rights activist Tarana Burke in 2006. After the Weinstein scandal began to go viral, and celebrities started using the hashtag, Burke feared that the initial goal of her message might potentially be lost, and shared the story of its origin with The Washington Post. Herself a survivor of multiple childhood sexual assaults in the low-income housing project where she grew up, she tweeted that #MeToo was “beyond a hashtag. It’s the start of a larger conversation and a movement for radical community healing.” Specifically, when working at a youth camp in Alabama, a girl in her early teens by the name of Heaven grew particularly attached to Burke, confiding in her counselor about the sexual violence she had herself suffered. Burke “was not ready” for this conversation and referred Heaven to another volunteer. The original Me Too was born when Heaven abandoned the camp never to return, and Burke’s inability to assist her young charge wracked the activist with guilt. “Why couldn’t you just say ‘me too?’” became her battle cry. Over ten years later, she wanted more than anything to ensure that #MeToo (in its online usage) would be more than a flash in the pan of celebrity news reporting and would spark a wider dialogue, particularly with men, about the incredible pervasiveness of sexual misconduct. Burke fought to ensure that her story—and Heaven’s—would not be silenced.

As a woman who has been as disturbed as many of us by the fallout from Harvey Weinstein’s disgrace (one is hard pressed to say whether he or Milverton is the more repugnant figure), I have contributed to multiple painful but necessary public conversations regarding #MeToo. Because #MeToo is ultimately about survivors’ voices, it does not seem out of place for me to say that I have twice been (albeit briefly, and escaped both times) kidnapped by cab drivers who wanted to take me somewhere entirely other than my home, touched inappropriately, and solicited for sexual favors in return for being “mentored” in the world of mystery fiction writing. While hardly any women of my acquaintance were shocked at this news, plentiful good men came forward to say they were appalled, disgusted, and wished in future for us to consider them allies in the war against sexual assault—allies like Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, both men of honor who genuinely abhor seeing women harmed.

At one point during this painful but necessary dialogue, a curious question arose. We are already familiar with Watson’s dismay when he learns that Holmes has become engaged to Milverton’s housemaid under false pretenses. We would expect nothing less from the utterly scrupulous doctor, and unfortunately cannot be too surprised that the cold-blooded detective threw himself into the heady business of winning at any cost, especially against such a loathsome foe. But following the movement largely responsible for revealing that most females are bound to be treated as disposable at some point in their lives, to what extent do we need to reevaluate Holmes’s callous—although, to him, morally justifiable—actions? Was Holmes culpable in any fashion? Was there another, better way of proceeding, or was he instead faced with no choice?

According to the sleuth, the end entirely justifies the means (a phrase generally attributed to Nicolo Machiavelli’s commentary in The Prince, but first probably expressed by Sophocles in Electra when he wrote that “the end excuses any evil”). Holmes claims that consideration of the girl’s feelings is unnecessary because he has a hated rival who will swoop in the moment Holmes’s back is turned. To anyone who has ever fallen hard for a charming newcomer who happens to be pulling out all the stops, this excuse is at worst laughable and at best hopelessly naïve. While one cannot imagine Holmes taking any physical advantage of his paramour whatsoever—indeed, he makes a point of assuring Watson that the extent of their association has been confined to walking and talking—surely going as far as an actual marriage proposal could not have been entirely necessary. On the contrary, it smacks rather of Holmes’s well-documented yen for theatrical parlor tricks along the lines of hiding treaties in curry dishes and masquerading as old booksellers. If Holmes had been operating without an audience, there is no doubt in my mind that proceedings would have ceased well before the contractually binding phase. I can only surmise, however, that in the course of an otherwise abysmally dark investigation, the prospect of announcing his engagement to Dr. Watson must have been cheering in no small degree.

Let us assume, then, that Holmes can be accused of insensitivity bordering on the incredible, but never of predatory designs. He is, in fact, seeking actively—at immense personal risk—to prevent a predator from hunting his prey unchecked. Lying to maids rather than marching down to the housing offices to research floor plans is doubtless morally wrong. But Holmes and Watson almost immediately abandon all talk of the unnamed servant girl to enter a parallel discussion; Holmes proposes to burgle Milverton’s lair. Housebreaking is also immoral (under most circumstances), arguably no more or less so than stealing a man’s pocketbook by force, but Watson hardly needs to consider the matter before conceding Holmes’s point: the end excuses any evil. It is almost impossible to disagree with either man. How many acts of a dubious ethical nature was Holmes forced to commit during his dismantling of Professor Moriarty’s network, and how many lives were saved as a result? At the very least, Holmes was guilty of tossing an elderly maths professor off a cliff in Switzerland. (While self-defense could surely be argued beyond any reasonable doubt, one wonders whether it’s quite cricket for a talented boxer and “baritsu” student to go hand to hand with an opponent better accustomed to lifting chalk and erasers.)

Much more disturbing to me is not that Holmes duplicitously flirted with a housemaid, or even that he got a trifle carried away with his performance—it is that two reasonably well-off men of independent means could forget any consideration of her after expending a mere few sentences on her welfare. The tale of the housemaid is not the tale being told to us; like the stories of Tarana Burke and her young friend Heaven, the maid’s narrative is disposable, and as such, is now lost to the mists of time. After obtaining her degree from Auburn University, Burke helped to found Just Be Inc, which combats the issue of erasure by encouraging young women of color to believe in their own intrinsic value. “When they’re not in this circle or in this room, they’ll go out into this world that’ll constantly try to devalue them, and they need to be grounded in something that constantly brings them back to their worthiness…” Burke told Vibe.com in a feature interview. One hopes that Holmes’s former fiancée emerges from her broken engagement, her employer’s burgling, and his subsequent murder without any enduring scars. The unfortunate but undeniable truth is that neither Holmes nor Watson bothered to tell us if that were the case.

My point here is hardly a subtle one, though it is darkly ironic. The preservation of Lady Eva Blackwell’s engagement is important to both Holmes and Watson, in fact drives all their actions; the preservation of the nameless maid’s engagement is of no import whatsoever. Both are offers of marriage accepted in good faith, but the housemaid’s dreams of the future must be sacrificed (indeed, exploited) in order to preserve the heiress’s. I would argue that this is not an example of misogyny on Holmes’s and Watson’s part, but instead of rampant classism. The housemaid is not even the only member of a lower economic strata who falls victim to Victorian snobbery during the account. Recall that Lady Eva is a beautiful debutante who made the cardinal error in judgment of writing to an “impecunious young squire in the country.” These terms are simply coding for the fact that her affections were directed at a man who was poorer than she. And as a comely young maiden, Lady Eva’s intrinsic value lies in not who she is, but who she marries. Now slated to be wed to the much more impressive-sounding Earl of Dovercourt, one wonders to what extent her early correspondence could have consisted of genuine love, or frank sexual attraction, and what if any role her parents played in redirecting the course of her life and affections.

Parental control over unmarried women in the higher echelons of society was during the time period in question nearly absolute. While this by no means guarantees or even suggests that Lady Eva’s authority figures were cruel to her, it does bring up a point seldom made: while Lady Eva was terrified of her reputation being forever sullied, and all prospects of running a respectable household of her own were assuredly threatened, her country squire could as easily have been the love of her life as a fortune-seeking knave (and in this manner, Lady Eva’s story arguably proves just as peripheral to the plot as the hapless housemaid’s). Fortunately, the accepted medical opinion in the late 19th century was that normal, healthy women had no interest in matters “sprightly” whatsoever, as eloquently explicated by Dr. William Acton in his 1870 study of prostitution and its deleterious effects:

…There can be no doubt that sexual feeling in the female is in the majority of cases in abeyance… The best mothers, wives, and managers of households know little or nothing of sexual indulgence. Love of home, children, and domestic duties, are the only passions they feel… A modest woman seldom desires any sexual gratification for herself. She submits to her husband, but only to please him; and, but for the desire of maternity, would far rather be relieved from his attentions.

Therefore, the modern reader need not concern oneself in the slightest over whether Lady Eva’s fondest wishes actually came true following the Milverton debacle. Other than making a profitable match and bearing healthy children, she never had any in the first place.

Much more importantly, the reputations of housemaids during the Victorian and Edwardian eras were scrutinized to the minutest degree. An amoral individual himself, possibly Milverton had no interest in what his maids got up to and whom they deigned to walk about with after hours. Surely there was a housekeeper who did pay attention to such scruples, however, to say nothing of the jilted sweetheart who may have demanded an explanation regarding why he was treated so cruelly. As Victorian social historian Henry Mayhew reported:

Maid-servants seldom have a chance of marrying, unless placed in a good family,

where, after putting by a little money by pinching and careful saving, the housemaid may become an object of interest to the footman, who is looking out for a public-house, or when the housekeeper allies herself to the butler, and together they set up in business. In small families, the servants often give themselves up to the sons, or to the policeman on the beat, or to soldiers in the Parks… They are badly educated and are not well looked after by their mistresses as a rule, although every dereliction from the paths of propriety by them will be visited with the heaviest displeasure, and most frequently be followed by dismissal of the most summary description….

Our housemaid’s position after Holmes abandons his Escott persona is not merely tenuous; it is downright perilous. It is not a far stretch to imagine her abandoned by her former suitor and in very real danger of losing her livelihood without being given a character reference. The fate of such women, ejected from not only their occupations but their lodgings when faced with being sacked, was often destitution, prostitution, or even death. One cannot imagine Holmes’s fiancée is trained in typewriting or music teaching. Nor is it likely she has wealthy relations on whom she can rely. She is a manual laborer, hands scabbed and roughened with lead-black and lye and astringent cleaning materials, a poor woman scrubbing the front doorsteps of a rich sadist, whose best hope for a good future lies in a happy—or at least, not distasteful—marriage.

None of these worries even occur to Holmes or Watson, safe at Baker Street by the fire and planning their knights-in-shining-armor campaign. Neither does it cross Holmes’s mind that when he described himself as “a plumber with a rising business,” the housemaid could easily have considered her own economic situation and chosen what she imagined would be a life of stability rather than penury. We have no notion of Holmes’s rival’s profession (though as Mayhew indicates, footman or groomsman or other household worker is likeliest), or even any idea whether he treats his sweetheart well. He could be a man given to drink, a man often under-employed or out of work, or in countless other ways a less desirable option than Escott. No one would dream of making the ludicrous argument that Holmes was overly experienced at the art of seduction; but his effect on women when he wanted to be charming was reported by Watson as soothing to the point of mesmeric. He could easily have made a better case for himself than his rival could do. We will never know the truth of why our housemaid choses Holmes over another man. What we do know, however, is that our protagonists’ lives are so very removed from that of a housemaid that they spend around fifteen seconds discussing her before switching to talk of the weather.

The entire problematic plot of this adventure is thankfully redeemed, resoundingly, by the true heroine of the tale: the veiled woman whose life Milverton ruined. She describes with heartbreaking passion having begged and prayed for the blackmailer’s mercy, been rebuffed and tragically humiliated, and then proceeds to empty five shots from a gleaming little revolver into her enemy’s chest. It turns out that, while Holmes and Watson admittedly contribute to the destruction of the incriminating documents in Milverton’s safe, they are not needed to bring the matter to a successful conclusion. Our two gallants are, in fact, delightfully superfluous. The veiled widow pours out her soul (and a striking number of bullets), escapes Scott free, and doubtless expends as much guilt on her successfully executed murder as Holmes spends on his ex-fiancée. This arguably makes Milverton’s killer the perpetrator of the single most dramatic and deserved extermination of a human pestilence in the entire canon. Whatever the ranking, she is deserving of our enthusiastic applause.

One hardly enjoys seeing Sherlock Holmes behaving less than ideally. But in Holmes’s defense, he never for a second considered coming up with a more prudent plan of attack that would have been of less risk to his life and his professional reputation. On the contrary, after being warned by Watson they very likely could both end up in jail over this escapade, he still considers doing what he believes to be right more important than potential damage to himself—or still more consequently, his friend. No, if the story we are being told is entirely about the Great Detective and the Good Doctor, then we can forgive them for mistakes made out of abundance of enthusiasm. Whoever heard of Sherlock Holmes, of all people, getting carried away?

The question we must pose ourselves in a post-#MeToo society is: whose story isn’t being heard, and why might society cause this to be so? In her feature interview for Vibe.com, Burke goes on to say:

When we initially got started, it was about giving these girls language so that they could adequately describe what they’d experienced. You could have pain without having the words to describe it, because no one taught it to you. So we started off giving them language, then, we gave them possibility. I could stand up and say, ‘I’m Ms. Tarana, this happened to me, too.’ And that always got them. That was the hook.

While neither Lady Eva nor the unnamed housemaid speak a single word in “Charles Augustus Milverton,” I can still admire the narrative for a number of reasons—including the fact that Milverton’s assassin does. She speaks her heart, pithily and with poise, and she does so while facing the man who did not merely ruin her, but refused to listen to her pleas. Perhaps it is not, after all, the five bullets emptied into the torso of a soulless blackmailer we ought to admire about this veiled woman, although such an act must have required unspeakable suffering, desperation, and courage. Perhaps instead what is most admirable about her is her stating clearly—and regarding complete strangers to her—that Milverton “will ruin no more lives as you have ruined mine. You will wring no more hearts as you have wrung mine.” In that instant, as clearly and powerfully as I have ever heard anyone speak, Milverton’s brave murderess declares, “Me too.”

Lyndsay Faye is the author of several novels, has been translated into 13 languages, but remains in love with English. You can find out more about them at lyndsayfaye.com & poke her on twitter @LyndsayFaye.

BSB Lyndsay, ASH “The Fascinating Daughter of a California Millionaire,” BSI “Kitty Winter.”

Brilliant. I have always found it questionable that Holmes was truly certain another suitor was waiting in the wings, so much as wished Watson would get off his case. Our heroes are far from infalliable,

(On a personal note, I hope you will consider discussing this lack of concern as part of the 221B Con panel on not excusing the problematic aspects of discrimination in canon.)

LOVE this!!!! First, I don’t think I have ever read this Holmes story, when I thought I had read them all. So thanks for that!

Second, I love how you showed the parallel treatment based on classism. One of the things I liked about ACD/Sherlock is that unlike his contemporaries you could not always pick the perpetrator by whomever is the lowest born. But even ACD/Sherlock has his own areas of blindness and failure. And that is important to realize. That people aren’t one dimensional cardboard cutouts that are stamped Good or Evil. That someone can be good most of the time yet still have an area of personal failure that needs to be addressed not ignored. The centerpiece of Burks original #MeToo movement was on COMMUNITY healing. That women need to be healed and for that to happen men have to be held responsible for what they do, what they encourage and what they chose to ignore.

Nice to know the BSI thinks society will so quickly reach a point where men no longer abuse their power, access, and position over women that this article will quickly be unrelatable.

Thank you for this thoughtful take on a disturbing case.

I like the way Jeremy Brett portrayed Holmes in this production. Holmes committed a treacherous deed to get at the villain. That does not say much for Holmes character. As much as I like to idolize the man, that is a place that I could not go. In Doyle’s defense, Holmes is never really displayed as an ideal person. Though in some respects Holmes is at times almost super-human, at other times he is all too human, and fraught with less than desirable traits.

Maybe Doyle redeems himself a bit by allowing the woman to slay her tormentor. Also, Holmes has been bested by women in the past, and on a regular basis by Mrs. Hudson.

Happy Trails!

What I would dearly love to know is exactly what they intended to convey by having Aggie(and I’m both surprised and disturbed to discover that she wasn’t always called Aggie, I would have sworn I’d read and re-read the story specifically to confirm her name but I checked again and she is, indeed, nameless) remember what he’d said as the plumber in voiceover while looking at him as himself. It feels deeply significant that she recognised him but didn’t say anything. I can’t immediately see the specifics of the significance, though.

Wow. That was a fantastic essay and it absolutely deserves to be published and widely read. Thank you so much for sharing it.

John and I thank the Baker Street Babes for you support of Lyndsay’s article and quick response in posting it. We think it’s not only a brilliant piece, it’s an article that will benefit many be they Sherlock fans or not. It’s obviously timely. Feminism looked very different in my day,but I was a part of that movement. The gains we made then were tiny in comparison to events taking place now. We appreciate all The Babes and the hard work you all do. You are helping to build the wave of change in society with intelligent work, keen observations and a zest for life ! Thank you. Bye the way, I just tried to donate funds to you and have encouraged others to do so too. When I hit the “donate” button” nothing happens. Help !

Hello Victoria, have you tried the button again? It works for me at the moment (I think Kris fixed it). Thank you!

Thoughtful and extremely timely. Thank you for sharing this and for treating the subject with the respect it deserves.

Sadly, Lyndsay Faye and others have assumed that Alice has no agency in this matter, one that a close reading of the story can refute. “You can’t help it, my dear Watson. You must play your cards as best you can when such a stake is on the table. However, I rejoice to say that I have a hated rival who will certainly cut me out the instant that my back is turned.” One can justify this scenario: Holmes arrives at Appledore Towers as Escott the plumber with only the idea of getting the lay of the land. Alice, who is in a long-term engagement that’s not going anywhere, sees Escott as a catalyst to spark a flame out of a low burning ember. Perhaps the hated rival is right there in the household. Holmes uses this hand that’s dealt to him, knowing that his actions will have little effect on Alice personally. As Holmes might caution, we do not have all the facts on what when on between Alice and Escott. Further, whether we are dealing with “ancient pockets filled with dinosaurs” or “window-breaking Furies” the Babes should know that they are not dealing with “men afraid that if they let the ladies speak their minds just a little too much, people won’t be able to handle it,” otherwise the Babes would not have been embraced by sections of the BSI so quickly and warmly as they have been. I realize that I look at this through the white male lens that I was born with, but the editors did not dismiss Faye’s piece with a rote “this does not meet our current needs” but the manuscripts series book will “have a limited distribution” while suggesting that her article deserves “prompt and wide-spread circulation” which, in fact, Faye’s name would insure the piece would have. As Faye also knows, editors sometimes have to make tough calls and I don’t see this as a pat-on-the-head dismissal, but what do I know (besides my personal knowledge that sexual abuse knows no boundaries of gender)? I do think that the Babes have overestimated the gender politics of this specific event, but again what do I know?

[…] Lyndsay Faye’s Milverton essay […]

Dear friends,

I first read all the canonical tales some 65 years ago–and have reread them, including MIL, on countless occasions since. From fairly early on, Holmes’s treatment of the housemaid struck me as callous, presumptuous, and potentially hurtful. So I fully agree with Faye’s conclusions, likewise her dismay at Watson’s milquetoast support of that treatment.

What’s more, the remainder of Faye’s analysis was a revelation: she raised issues I’d missed in all my re-readings, weighed the narrative’s established facts, acknowledged its nebulous ones, balanced hypotheses, and offered her findings with non-threatening clarity, objectivity, and restraint. Hence I don’t see how anyone can disagree (unless, like “James” above, you’ve concocted your own back story for the tale, then are offended that Faye didn’t know about it). Again, any calm, compassionate, streetwise reader should have no difficulty with her essay. I don’t. And I’m astonished that BSI did.

And I’m further astonished that the value and purposes of the Me Too movement should disturb BSI. The underlying principle–that of a victim in recovery helping to heal another victim–has been accepted in U.S. therapy for many decades … e.g., as practiced in America’s many 12-step programs. When AA, back in the 1940’s, spoke of “sharing our experience, strength, and hope,” that’s what they meant.

No question, these dark, mortifying sexual issues have been surfacing with greater intensity in recent years, not only incessantly in the news, but in the many health and recovery programs taking them on. BSI please pay close attention.

Thank you, Ms. Faye, for your impeccable and invaluable article!

All the best,

Rick

Frederick Paul Walter

Albuquerque, New Mexico

It almost becomes the trolley problem – destroy the reputation and prospects of one housemaid, or allow the destruction of the reputations and prospects of multiple blackmailing victims.