Femme Friday: Beryl Stapleton

If I were to ask you to list the three Canonical women who have appeared on screen most frequently, I bet you’d get two out of three. “Mrs. Hudson!” you might cry first, and you’d be right; Mrs. H. always seems on hand, regardless of the adventure and far outnumbers any other woman for appearances on screen. “Irene Adler!” you’d no doubt add, and that’s likely true, as she’s the go-to female foil for Holmes and is adapted into far more tales than her one Canonical appearance. For the third, you’re probably tempted to say Mary Morstan, but unlike Irene, she rarely turns up outside the context of The Sign of Four, and a glance at Sherlockian filmography (a more complete one than IMDb presents) indicates that Sign is the second most adapted tale—outnumbered as much as four times by film and television versions of that most beloved of stories, The Hound of the Baskervilles. The woman at the center of Hound, then, earns the third spot on our list: Beryl Stapleton.

Like Mrs. Hudson, Irene, and Mary Morstan, Beryl Stapleton has turned up enough times that her role in the story, her personality, her behavior, and even her appearance, do not always correspond to the Canonical Hound, but if we’re going to get a clear picture of this cunning and mercurial woman, we should start there. (Spoilers ahead!)

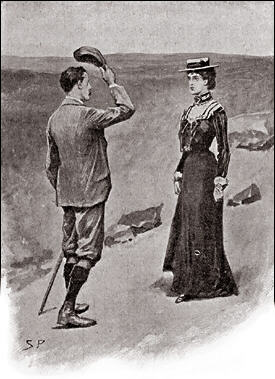

Beryl makes her first appearance nearly half way through Hound, when, thinking he is Sir Henry Baskerville, she appears on the moor to warn Watson of the dangers he faces if he doesn’t immediately return to London. Watson, with ever the eye for a pretty face, describes her as “a beauty…of the most uncommon type.” She is “darker than any brunette whom I have seen in England—slim, elegant, and tall” with a “proud finely cut face,” “sensitive mouth,” and “beautiful, dark, eager eyes.” “With her perfect figure and elegant dress,” he adds, “she was, indeed, a strange apparition upon a lonely moorland path.” Steady, Watson. She’s totally going to be a love interest, but not yours. Keep it together.

Their little tête-à-tête is cut short by the return of Jack Stapleton, Beryl’s “brother” (wink-wink), but one more curious thing happens. Stapleton offers this offhand remark: “And yet we manage to make ourselves fairly happy, do we not, Beryl?” to which she replies “Quite happy.” Watson, who may be slightly more observant than we give him credit for, poor chap, notes that “there was no ring of conviction in her words.” This is Beryl in a nutshell: she is a woman trapped, a woman in conflict, a woman, in short, who wants to do the right thing, but is daily in fear for her life. Beryl Stapleton is clever, and she has the strength and will of ten hell hounds.

Their little tête-à-tête is cut short by the return of Jack Stapleton, Beryl’s “brother” (wink-wink), but one more curious thing happens. Stapleton offers this offhand remark: “And yet we manage to make ourselves fairly happy, do we not, Beryl?” to which she replies “Quite happy.” Watson, who may be slightly more observant than we give him credit for, poor chap, notes that “there was no ring of conviction in her words.” This is Beryl in a nutshell: she is a woman trapped, a woman in conflict, a woman, in short, who wants to do the right thing, but is daily in fear for her life. Beryl Stapleton is clever, and she has the strength and will of ten hell hounds.

Here’s the thing about Beryl Stapleton: she has it rough. She married a suave crook in her native Costa Rica (insert obligatory apology for ACD’s casual and consistent racism toward Latinas, and for filmmakers who often feel the need to recast her as a blonde haired, blue eyed English rose) and followed him through a series of illegal operations. Was she part of his nefarious plots? Probably. We learn later that he abuses her both emotionally and physically, though, so it’s hard to judge her for that—she’d have found little sympathy from the authorities as a foreigner and an abused married woman in 1889; she didn’t have many options. Once settled on the moor, she is forced to pretend to be her husband’s sister, which means Stapleton essentially planned to pimp her out to a series of Baskervilles in order to get his hands on the manor, title, and fortune. As Watson notes, Stapleton is a two ton pile of hound shit. (I am paraphrasing slightly.)

Although she is stuck pretending to be the unmarried Miss Beryl Stapleton, to her credit, she draws the line at luring kind old men to their certain deaths, and refuses to throw herself at Sir Charles. She also does what she can to warn off Sir Henry—going right to the edge of mortal danger. On one hand, she doesn’t want to be complicit in murder. On the other, she loves her husband and also fears him (“they are by no means incompatible emotions,” Holmes notes). She lives on the razor’s edge, caring for Sir Henry, enduring savage beatings from Stapleton, and deceiving everyone on every side to stay alive and keep her dignity. She plays a dangerous game. In the end, she turns on her murderous husband, and Holmes concedes a detail that we often forget: if the detective and the doctor had not solved the mystery when they had, Beryl, who had all the information from the start, would have gone to the police in any case. Holmes and Watson who?

I mentioned that Beryl has appeared on screen enough to grow beyond the story that Conan Doyle wrote for her. Her role has been fundamentally different in several versions of Hound, and the role she plays often defines the whole character of the adaptation, which speaks to her place as a lynchpin in the most popular Sherlock Holmes story. I’ll spare you the hours it would take to rehash every version and just offer three.

In 1939’s Hound, starring Basil Rathbone, Beryl was stripped of her backstory—she really was Stapleton’s sister. This let the romance she had with Sir Henry pass the censors (the Hayes Code prohibited films from suggesting that any good, like, say, marrying the gorgeous baronet and gaining happiness, wealth, and title, could come from adultery. Obviously married women in abusive relationships with murderous crooks must stay that way because Morality.) This Beryl, who presumably got to live happily ever after, may hold the honor of being the only woman in any role ever to be billed above both Holmes and Watson in a Sherlock Holmes movie. Like I said: Holmes and Watson who?

Hammer’s marvelous B-movie from 1959 re-imagines Beryl completely. She is restored to her Spanish roots, transformed into Stapleton’s daughter, and is renamed Cecile for good measure. She appears young, wild, barefoot, and boobilicious, and although this film is totally enjoyable anyhow, it’s worth watching just to see her charm Christopher Lee’s basso profundo clean off, and leave him silent and glassy-eyed. (Christopher Lee snogging, anyone? Just me? Ok.) Of course, in becoming Stapleton’s daughter, she also becomes a Baskerville, not an unwitting and misused accomplice, but the mastermind behind the plan to kill both Sir Charles and Sir Henry. Instead of a fairytale romance, she gets a slurping trip to the bottom of the Grimpen Mire, but damn did she have some agency before she went.

1959 was not the only year Miss Stapleton met a bad end. There is a bit of intra-Babe conflict regarding the made for TV version of Hound from 2002 starring Richard Roxburgh. (and by intra-Babe conflict I mean that Lyndsay and I once stayed up until silly o’clock drinking rum and debating its relative merits: she despises it almost as much as Matt Frewer’s eyebrows; it’s one of my favourites.) I think it handles the climax in a more thrilling way than any other. This climax includes Richard E. Grant’s impeccably slimy Stapleton announcing “I have no wife” with chilling calm, several times over, as Holmes presents his evidence and Watson frantically searches the house for Beryl. Watson finally finds her, beaten and hanged in an outbuilding. In his blind Watsonian rage, he rushes in and attempts to kill Stapleton, which precipitates the rest of the action. Even in death, Beryl is the center of the action.

Sometimes villain, sometimes victim, Beryl Stapleton is one of the most complex women in the Sherlock Holmes Canon. She drives Sir Henry wild, drives Stapleton to distraction, and above all, drives the plot no matter what part she’s given to play in it. So next time you’re making a catalogue of Canonical ladies, make sure that Beryl Stapleton is near the top. Because you sure as hell don’t want to be on her bad side.

Ashley D. Polasek holds a PhD in English, with a specialty in adaptations of Sherlock Holmes, a subject on which she has published in Adaptation, Literature/Film Quarterly, Transformative Works and Cultures, Viewfinder, and The Journal of Victorian Culture Online, among others. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and an Honourary Research Fellow at the Centre for Adaptations at De Montfort University.

Ashley is the co-editor, with Lyndsay Faye, of Behind the Canonical Screen (BSI Press, 2016) and the co-editor, with Prof. Deborah Cartmell, of The Blackwell Companion to the Biopic (Wiley-Blackwell, forthcoming 2018). You can follow her on Twitter @SherlockPhD

Hello. I am a Costa Rican woman, a passionate reader of 19th English literature, and a fan of Beryl Stapleton for obvious reasons. I have a question, and perhaps you can help me: what would her legal situation have been in 1889 England after the events in “Hound”? Would she have to answer for the crimes she and her husband committed, both under the Stapleton and the Vandeleur names? I think she would not have wanted to come back to Costa Rica after bringing disgrace upon her family here, and with a possible jail sentence waiting for her as her husband’s accomplice in the embezzlement of public money. I oftend wonder what became of her.

We stumbled over here coming from a different page and thought I should check things out. I like what I see so now i am following you. Look forward to looking over your web page for a second time.

The question is, did Beryl Stapleton and Sir henryBaskerville get together again when he returned from his round-the-world trip with Dr. Mortimer? She might have gone with them as Sir Henry’s nurse or waited at home for his return. Or his disgust at her role may have put him off her for life.

Any ideas, Ashley and Lindsay?

Please let me know.

Thank you and best wishes, Luke Wiseman