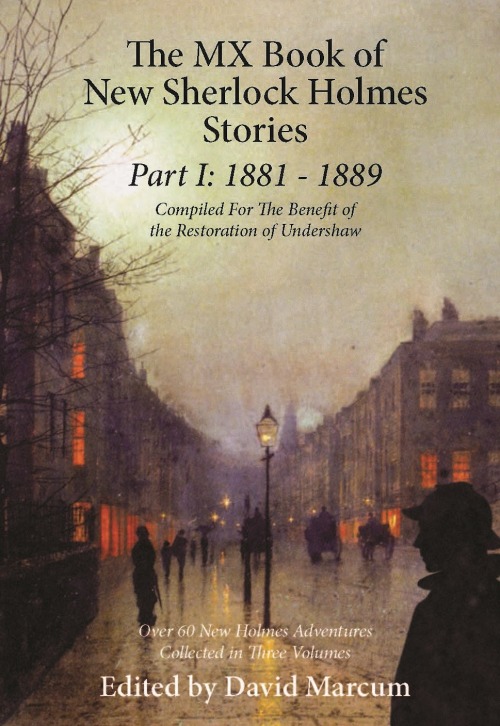

Interview with David Marcum, Editor of The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories

Exclusive interview with MX Anthology editor David Marcum, who has compiled the largest assembly of Sherlockian pastiches ever in order to benefit Undershaw preservation!

The Babes put our heads together and asked David a number of questions. You can still contribute to the Kickstarter as well, and thank you for all your tremendous support of this very worthy project!

DAVID: First of all, thank you for the opportunity to answer these questions, giving me a chance to explain some of the thinking that went into creating and editing the new anthology, The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories, and also to share my thoughts, as both a die-hard Sherlockian and a sometime “editor” of Watson’s notes, about Canon and pastiche.

From Maria:

How do you update the material and still keep true to the Canon?

DAVID: To me, the Canon is The Fixed Point. Any new stories that I would want to read should exist within the structure of the originals. Those original stories are the steel beams and framework of a skyscraper, set on solid bedrock and supporting whatever additional construct (pastiches) is hung upon them, with lots of room and open space all around them to fill in other details. But those pastiches must be in accordance with the Building Code as established by The Canon.

To be more specific, a new Holmes story that I want to read (or write) can be narrated by Watson or some other character, or it can be in omniscient third-person. It should be set within the lifetime ranges of the historical Holmes and Watson, men who were born in the 1850’s and lived into the 20th Century. The characters cannot be uprooted and modernized, for if they are moved to different eras, whether it’s the present or the ancient past or three hundred years from now (as has been done in some Star Trek stories,) they are not the correct Holmes and Watson who were born in the Victorian era, and thus the stories are no longer about Holmes and Watson. The characters should use the language and technology available to them during the appropriate timeframe – no time machines or overblown supernatural encounters with Dracula – and their behavior should match that established in the original Canonical stories as well.

So really the answer to your question is in the question itself: Keep true to the Canon. When I asked authors to contribute to this new collection, I made a point of stressing that these stories should be traditional and Canonical. Some submissions didn’t make the cut. What is presented in in this collection is good old-fashioned Holmes and Watson.

How liberal are you in your interpretation of Canon material. Do you change canonical “facts” to fit your stories?

Good question, and apologies for the even longer answer. First of all, I play The Game with extreme devotion, and if Holmes and Watson are not presented as historical figures living in the correct periods, then to me the stories are not actually about Holmes and Watson at all. I don’t like to see Holmes in flat-out supernatural stories where he is a substitute for Van Helsing – although a little supernatural “What if?” is okay sometimes – or as a different kind of Dr. Who, to be reincarnated in whatever form that a particular generation needs him to be.

Having said that, I do appreciate some growth and interpretation within the Canonical framework, and pastiches are the way to do this. I grew up reading pastiches before I had even read most of the Canon, so to me Canon and pastiches are indivisible when looking at the lives of Our Heroes.

My initial meeting with Holmes was when I was ten in 1975, with an abridged copy of The Adventures and the last half of A Study in Terror on television. Soon after, I read Nick Meyers’ books The Seven-Per-Cent Solution and The West End Horror. By then, I knew enough to realize that parts of The Seven-Per-Cent Solution were accurate, and others, such as when Professor Moriarty is painted as a harmless old man, had obviously been written by the Professor himself and grafted onto Watson’s notes. Early on, I also found old Rathbone/Bruce radio shows at the library, some Canon adaptations but mostly pastiches. I was given Baring-Gould’s biography, Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, around the same time that I discovered Holmes, and while I don’t agree with everything that he proposes, a lot of Baring-Gould’s ideas are rooted in my head and make a good jumping-off place. For instance, I didn’t even know who Nero Wolfe was when I first read B-G’s biography, even though he was identified in the book as Holmes and Irene Adler’s son. Now, Nero Wolfe is my favorite all-time character after Holmes, and I have no problem with this connection. That’s definitely an example of stretching the Canon. All this goes to show that I enjoy filling in the gaps in the Canon without abandoning it.

I’ve been maintaining an extremely extensive Chronology of both Canon and pastiches since the mid-1990’s, now listing thousands of adventures. It’s broken down by day, and sometimes by hour, and each story that’s included is arranged by chapter, page, or even paragraph. (Some people have seen samples of this Chronology, but it’s not ready for publication yet – if ever.) As part of that whole process, I have subjective notes where certain aspects of the various stories are listed as incorrect in relation to the big picture. (Someone might write that Watson is living in Paddington when he is actually living in Kensington during the time of that particular story.)

By having such a broad perspective in my mind of the overall lives of Holmes and Watson, from births to deaths, I can see how some things do or don’t fit together. This gave me a good idea while editing and accepting submissions for the anthology of what was straying too far from traditional and into an Alternate Universe.

If someone happened to submit a story with minor problem, such as Watson living in Paddington when he’s supposed to be in Kensington, the author and I worked it out. But some stories were rejected entirely – no one was assured of an automatic inclusion in the anthology just because they took the time to write and submit something. If someone had tried something crazy like making Irene Adler a murderer, I would have had to tell them, politely, sorry but I can’t use it, as I just cannot let Irene be portrayed that way. It’s just too far into the weeds.

What is the most difficult part of writing a Holmes pastiche?

When I’m writing a story, I have to avoid letting modern language creep in, and more specifically, letting my American ignorance put in things that, to a British reader, are ridiculously incorrect and yank one right out of the story. In the first edition of my first book, I made a passing reference to Mary, Queen of Scots, not even realizing that I was taking about the wrong Mary. (I received a nice email about it, and it’s been fixed in a subsequent edition.) Also, I’ve learned to be more careful about describing old-time British cars, how I refer to London street intersections, and the differences between telegrams and wires and telegraph offices and post offices.

When writing my own stories, I’ve given up on trying to put in British spellings, because I know that I’ll find some and then miss others, leading to an embarrassing inconsistency. It’s better for me just to spell everything American, with an apologetic explanation in the foreword. (And after all, I rationalize, both Holmes and Watson spent time in the U.S., so they would certainly have picked up some American traits.) With this new anthology, I mention in the introduction that the participating authors are allowed to spell things as they like, since we have contributors from all over the world: The U.S., Canada, all around the U.K., New Zealand, India, and Sweden, and also two British ex-patriates living in Asia, and a couple of American ex-pats living in London and Kuwait.

What is the easiest?

For me, I just sit back and let Watson speak. I don’t write with an outline. The story might begin with a conversation in the Baker Street sitting room. I just type and record what happens. When someone climbs the seventeen steps and knocks on the door, I don’t know any more about the caller than Holmes and Watson do. (Well, Holmes actually knows quite a lot, since he’s already deduced many facts from footsteps and breathing and a dozen other things. As he explains what he’s learned, I happily transcribe it.) It amazes me to see the story unfold, and to learn Holmes’s solution right along with Watson. That’s part of why I love to write. I go into The Zone, and come back out four hours later with several new pages on my screen and all of my coffee gone. (That reminds me – I need to go get some more coffee. Be right back.)

Do you have Canon Holmes (Paget, Steele) in mind when you write canonical Holmes, or does your mind address a different Holmes (from another pastiche or adaptation?)

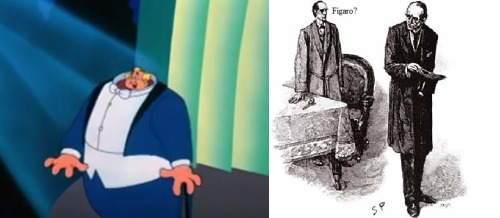

Absolutely 1,000-percent Paget, accept no substitutes. (Well, don’t accept that Paget illustration of Holmes and Moriarty from “The Final Problem”. That teeny-tiny pin-headed Holmes in that picture is rather disturbing. It’s like when the opera singer’s head shrinks after he drinks liquid alum in the Bugs Bunny masterpiece, “Long Haired Hare”.)

I know that the traditional American view of Holmes for the longest time was from Steele’s illustrations, by way of William Gillette, but my first idea of how Holmes should look was Basil Rathbone, based on photos from Holmes of the Movies by David Stuart Davies, a book I acquired when I was eleven or twelve. Later, my idea of how Holmes looked became more purified, and Basil Rathbone then just looked like himself, an actor who resembled Holmes a great deal. In terms of other actors, Holmes also looks a lot like Arthur Wontner and Douglas Wilmer, and maybe some Ian Richardson thrown in. But he doesn’t look like Iron Man or Khan.

In my head, I hear Holmes and Watson as Clive Merrison and Michael Williams. But during the couple of times that I’ve written scripts for Imagination Theatre, based on stories in my first Holmes book, I heard the phrasing and speech patterns of John Patrick Lowrie and Larry Albert.

From Ardy:

What is one pet peeve you have about pastiches?

DAVID: A general pet peeve is when people write new pastiches without doing any research, or without actually knowing anything meaningful about the Canon. So many people think they know all that they need to know from reading a few stories when they were kids, or from watching a movie or television show and remembering and tossing in a few tropes and clichés. Throw in a deerstalker and a big pipe and an “Elementary!” and a stupid Watson. These authors jump in to write a story and maybe make a little money, but they don’t know what they’re writing about.

I recall reading some stories by a certain author on fanfiction.net a few years ago. At one point, long after she had already produced a great deal of material, she announced that she had finally forced her way through the original 56 short stories in the Canon, but she had no intention of reading the four novels, as they were too long and boring. There’s no excuse for that.

To pick a specific pet peeve out of the deerstalker, I’d have to say that it’s very irritating when people say – with total sincerity throughout their work – that John Watson’s first name is “James”. (There are several inexplicable examples of this where he’s “James” throughout the whole book.) We know that Watson’s wife calls him that in passing in “The Man With the Twisted Lip”, and that it’s a nickname for his middle name, “Hamish”, but some people just remember his name incorrectly, or never really knew it to begin with, and they write their stories that way without ever checking back with the source material.

If I don’t read pastiche, what am I missing out on? (i.e. Explain in as much detail as you want why people should read pastiche.)

“Explain in as much detail as you want … .” Oh, you shouldn’t have done that.

Over the last few decades, I’ve been a passionate missionary for the Church of the Holmesian Pastiche. Once a person is aware of all the other stories about Holmes and Watson, the tiny fraction of the big picture known as The Canon is just not enough.

As I say in the introduction to the new anthology, and also in an essay in the Baker Street Journal from a few years ago, just sixty stories about the world’s first consulting are not enough to show why he is the world’s greatest detective. Everyone approaches Sherlockian enthusiasm by a different route. Some people love the scholarly approach, digging into various aspects of Victorian life or things related to Watson’s literary agent. There are enthusiasts that enjoy the stories, but it’s really a jumping-off place for socializing with other Sherlockians. Still others make a serious study of the original sixty stories, but want nothing to do with anything past that. (A few of these folks don’t even want to accept all of the original sixty stories into the Canon, pointing out this or that inconsistency that means a certain original story isn’t a legitimate entry.)

My interest in Holmes and Watson is all about the adventures – what Holmes and Watson did – and I want more of them. When I had the idea for The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories, I literally woke up early one Saturday, having just had a vivid dream about it. It was a way to be able to read even more Holmes pastiches.

I’ve been collecting pastiches for forty years now – wow, that went fast! – and I have thousands of them, in the form of novels, short stories, radio and television episodes, movies and scripts, uncollected manuscripts and comics, and fan fiction. It doesn’t matter to me if it’s a 600+ page book (like the one of up-and-down quality – but mostly up! – that I just finished on Thursday, The Fifth Heart by Dan Simmons,) or a 600-word fan fiction fragment that just covers a brief conversation. If a pastiche adds to and fills in areas between the traditional Canonical stories, then I want to know about it.

To show how pastiches add to the bigger picture, I’ll use a non-Holmes example, (unless you subscribe to the idea that Mr. Spock is Holmes’s descendant, based on a statement Spock makes in Star Trek VI. If so, then this sort-of is a Holmes-related example.) The Star Trek novels and comics fill in the cracks between the various film versions in much the same way that pastiches augment the Canon. These printed stories relate a number of Trek adventures that occur between and around television episodes and movies, giving extra information about both events and characters’ lives. For example, most people think that the events of Star Trek III: The Search for Spock feed directly into what happens next in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. What actually happens is that, after the events of Star Trek III, there is a long multi-year story arc that takes place in the Star Trek comics, relating what happens between the two films, before the characters end up back on Vulcan for the opening events of the fourth movie. You can see both films back-to-back with great enjoyment without ever knowing there is a big story that occurs in that crack. But once you do know that there is more story in there, it’s hard to ignore or forget it. Holmes pastiches are the same way. You can read (and re-read and re-re-read) The Canon and enjoy it every time, seeing something a different way through each pass. But if you know what else is happening, as told by pastiches set before and after and around and through the original stories, all adding extra depth and context, it’s hard to go back to just reading the Canon and nothing else.

I was always fascinated by something I read about the Star Trek publishing operations. There is apparently an office in New York that keeps a master timeline of the Trek universe. If you write a story or comic, it has to fit into the overall plan. (Of course, when the television shows were in production, whatever they came up with became the new canon, and the books had to be adjusted, rationalized, or explained in some way.) Authors are told that they can use the characters, but they have to put them back when they’re done, leaving them the way they were for the next person. That was one of the things that I told contributors when they were invited to submit stories for the new MX collection. Use Holmes and Watson in a traditional way, and when you’re done, leave them unharmed. Therefore, this new anthology won’t have any stories where 221 Baker Street burns to the ground and Holmes and Watson move permanently to North Gower Street.

What’s your favourite story/fact/book/object/thing you have come in contact with while researching pastiche?

This is a tough question. In terms of collecting, I can point out this or that book, or manuscripts (published and unpublished) that I’ve tracked down. My wife is a reference librarian with a Bachelor’s Degree and two Master’s, and she has taught me some really great research tricks to help winkle out obscure pastiches.

But as far as researching a pastiche? That I’m not so sure about. The first time I “edited” any of Watson’s notes was back in 2008, when I was laid off from an engineering job during the Great Recession. While I had the time, I was putting the stories down for my own satisfaction, and never thought they would be published. Therefore, there are a couple of stories (in The Papers of Sherlock Holmes Vol. II) where Holmes and Watson visit my hometown in eastern Tennessee in the early 1920’s. (It’s more plausible than it sounds.) For my son’s amusement, there are a lot of local sites thrown into the tales, and to make things more authentic, I ended up doing some local research to get things correct, such as finding the name of the real 1921 police chief. Later, when the book was published, I considered leaving these stories out because of their more personal nature, such as when Holmes and Watson interact with my grandparents, but in the end I let them stay. I’m glad now, because I’ve gotten a lot of positive feedback.

Later, I was able to make my Holmes Pilgrimage to England and Scotland for a few weeks in 2013. It was the first (and so far only) time I’ve been over there, and I spent weeks visiting hundreds of Holmes-related sites that I had researched for months beforehand, based on over a dozen Holmes travel books in my collection. (If it wasn’t about Holmes, I pretty much ignored it. I didn’t go on the Eye, because it has nothing to do with Holmes, but I did visit the Tower – not because of its historic or tourist value, but because so many great pastiches have been set there.)

While over there, I visited several places that I had already written about in my first books, using a little earlier research but having no true first-hand experience. I had a story in my first book called “The Haunting of Sutton House”, and on my trip, I actually went to Sutton House, which apparently really has a reputation of being haunted. I was glad to see that it matched my description. (I was wearing my deerstalker while there, which I wear as my normal everyday hat from fall to spring each year, and no one at the house questioned it. Also, I didn’t see a copy of my book lying around, so maybe they don’t know that I wrote about them and their ghosts.)

While in England, I scouted out a number of new sites that coincidentally ended up being in the stories in my most recent book. That made it extra fun for me. I initially wrote about Holmes and Watson coming to walk in my hometown, because I hadn’t yet made it over there to walk in theirs. After the trip, not only had I walked there, but I had identified new places for them to walk as well.

From Melinda:

The issue of cultural appropriation has been a hot topic lately. There has been a glut of new Holmes material coming out in recent years, ranging from by the book tributes to content that seemingly only has the names of the characters in common with the original stories. Do you think the surge in popularity of the Sherlock Holmes brand has led to more pastiche or more appropriation, and do you think there is a difference in the integrity between the two?

DAVID: I think that there is a fairly even split between current increases in both pastiche and appropriation, and the associated integrity, or lack thereof, is related to how closely the creators are willing to stick to the Canon. As you will have seen from my other answers, I prefer accurate pastiche of the true characters. I really have no use for appropriations of the character that use the famous character names to lure in readers or viewers, and then fling the characters off in entirely inappropriate directions – having Holmes murder someone, having Watson’s wife turn out to be a trained assassin, etc. People who only meet Holmes and Watson through these shows and don’t know any better, or don’t explore any further, will go away thinking that these are the real Holmes and Watson, and the characters are thus damaged and weakened because of it.

The surge in Holmes’s popularity in recent years can only be a good thing for someone like me who craves new pastiches, but it has downsides as well. The first is that, as I try to obtain and read every traditional adventure that appears – and I really do try to do that – there are literally new pastiches turning up almost daily, whether in the form of a book or a story on the web. When I was a kid, I was lucky if I could find two or three new Holmes stories per year – and then one of them might end up being something like The Last Sherlock Holmes Story, which was worse than no story at all. While there are a great many of the new stories that are of excellent quality, there are others where the “editor” of Watson’s notes did not quite have a full grasp of what is needed to sound completely authentic. These folks have their hearts in the right place, and it would be nice if all the new stories were perfect, but they can’t be.

On the question of appropriation, the behaviors and traits of Holmes and Watson have been lifted and used as a template for so many other characters now that it’s hard to keep track of it all. Certainly the most famous example of this right now is a BBC show called Sherlock, which features two guys that happen to have the same names as Holmes and Watson, and a few of the same biographical bullet points and personality quirks. However, even though there are a few similarities, they are not Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson.

I’ve said this in emails and interviews before: Imagine a new movie re-make featuring a character named Luke Skywalker, who lives in a dusty desert Old West town and meets a crazy old prospector/ex-soldier named Ben Kenobi. They find out about a girl that needs to be rescued, and they hire a roguish wagon driver, Hans, and his big hairy unintelligible tobacco-chewing side-kick (named “Chew ‘Bac’er”) to take them somewhere. Then, there is some big-shot with a pun-like name similar to Darth Vader who has a Death Train – kind of like the one in the Lone Ranger movie – and so on. The character names are the same or very similar, and there are all sorts of winks and nods to the original fans, showing that the creators are very familiar with the original material – as the Bard said, “The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose” – but if it’s not actually set in the stars, then it isn’t Star Wars anymore.

By the way, however, I’m really looking forward to the BBC Sherlock Christmas special, when Cumberbatch and Freeman will finally get to play Holmes and Watson for the very first time.

There are so many other shows that have appropriated Holmes and Watson. House was a great use of Holmes, which they acknowledged with little things for alert viewers, such as making House’s address 221b Baker Street, and giving him associations with Irene Adler and Moriarty. I understand The Mentalist, Backstrom, Monk, and Psych all had Holmesian elements, but I didn’t watch them. There’s apparently even a show called Elementary with a character named Sherlock Holmes, but I stay as far away from that one as I can, as one might expect.

The best appropriations of Holmes and Watson on TV now are Dr. Sheldon Cooper and Dr. Leonard Hofstadter of The Big Bang Theory. If you’re going to “borrow” Holmes and Watson, that’s the way to do it! (Actually, I really think they’re much more like the Sherlock and John of Sherlock than they are like the true Canonical Holmes and Watson.)

From Taylor:

Pastiche recommendations for those of us who enjoy hearing side characters’ (Mycroft, Mrs. Hudson, etc.) stories?

DAVID: Wow. So many things to suggest. There are a lot more pastiches out there about (or narrated by) the side characters than one might think. What follows is just a very small sampling, based on a quick survey of my Holmes shelves.

First, I’d have to mention Marcia Wilson, who started out writing fan fiction stories and novels under the name aragonite. She created a whole world that provides the backstory of Lestrade and the others at Scotland Yard. Her stories go from Lestrade’s first days as a constable to his retirement. Along the way, she builds up an incredible view of Watson, not as a side-kick of the great detective, but as a war veteran and husband who quickly gains the respect of all the Yarders. Initially her stories were at fanfiction.net, and most are still there. She pulled some of them off for her first two books, published at lulu.com. She’s now revised one of those books for her first MX release, You Buy Bones. I’ve been telling people about her stories for years, and I’m glad that she’s reaching a larger audience now. I’m also very happy that she’s written a new story for the MX anthology. As I often say, with her stories she’s found Scotland Yard’s tin dispatch box.

M.J. Trow has also written a number of stories about Lestrade, this time inexplicably naming him “Sholto.” They are uneven, and often portray Holmes and Watson as comedic buffoons, but there are some good threads in each story if one is willing to overlook the jabs at Our Heroes. Stephen Wade, a contributor to the new MX anthology, has also written several Lestrade tales which I hope will be appearing in book form in the future.

There are several authors that write Mycroft Holmes novels, including the pseudonymous Quinn Fawcett (not my favorites), and Glen Petrie (better). There are more series about the Irregulars – with many different combinations and members and Wiggins-es – than I can list right now. The new MX anthology has a story about Wiggins by Shane Simmons, and I believe that Shane enjoyed writing it so much that he’s going to produce some more, possibly for a new book.

There are a few series about Professor Moriarty, including one by John Gardner, and another by Michael Kurland, who has contributed a poem to the new anthology. Moriarty can also be found in Kim Newman’s Professor Moriarty, Anthony Horowitz’s Moriarty, and in a few stories in the new anthology by Summer Perkins, Robert Stapleton, and Sam Wiebe.

Gerard Williams wrote a couple of Dr. Mortimer novels, and I understand that there is a third one that was never published following Williams’ death that is still floating around out there somewhere. There are a few different series featuring Mrs. Hudson and Mary Watson as detectives in their own right, sometimes as the real detectives instead of Holmes, but these are so bizarre that I don’t intend to read them.

My Sherlock Holmes, edited by Michael Kurland, and Sherlock Holmes: Repeat Business by Lyn McConchie, each have stories related to side characters, and both Michael and Lyn have contributions to the new anthology. Barker, Holmes’s hated rival upon the Surrey shore from “The Retired Colourman”, has been fully developed in a series of novels by Will Thomas, who has contributed a Holmes and Watson adventure to this new collection. (I hinted to him early on that he include Barker in the new story as well, but Will didn’t take the bait. I suppose he’s reserving that special tale for one of his own future books.)

And one can’t forget the Irene Adler novels of Carole Nelson Douglas. All eight of them, with a few accompanying short stories, give such a wonderful picture of Irene that you will believe this is really her true story. (She’s not the scarlet woman or master thief or worse that is so often portrayed.) As an early reader of Baring-Gould, I accept the idea that Holmes and Irene had a later relationship (and a child, cough-cough Nero Wolfe cough-cough), and years ago I corresponded some about that with Ms. Douglas, who has contributed a poem to the new MX collection. She kindly pointed out that her novels about Irene occur pre-Reichenbach, so there is plenty of time for events to unfold in a way that will lead to the Holmes-Irene encounter.

That brings me to the end of the questions, and I won’t go back through them again or I’ll end up making the answers even longer. Thanks again for this opportunity, and I hope thateveryone enjoys the new MX anthology. The authors have all donated their royalties to the restoration of Undershaw, and I thank them so much for all their efforts.

Hellop

Could you pleased to give me the address or mail of

Mr C.Edward Davis

many thanks

B.decré