Femme Friday: Irene Adler

Irene Adler means many things to many people. For some, she is the first truly legendary antagonist faced by Sherlock Holmes. (Because really…do you spend much time ruminating over errant Mormons? Does Jonathan Small get your panties in a twist?)

For others, she is a plucky ringlet-haired sass machine who is allowed to tweak Robert Downey Junior by the nose, or a naked she-dervish who spanks her way to fame and fortune only to have it (questionably, maybe even egregiously) plucked away from her. For still others, she is a mere mask worn by that murderous maven Jaime Moriarty, whose half-smile never fails to break the brain of anyone who dares to look at Natalie Dormer without protective eyewear.

But who is Irene Adler, really? Or at least…who was she originally? And why do we love her so?

It would be ridiculous to say that we love Irene Adler because “To Sherlock Holmes, she is always the woman,” because pleeeeeeeze. Is this fact canonically true and completely awesome? Yes, indeed. Is it a bit of Watsonian ridiculousness? Thank you for asking, because this fella was not exactly the Encyclopedia Brittanica of narrators, and we have as much real evidence that Holmes gazed longingly at Irene’s printed selfie as we have that he was gently tipped off a cliff by an elderly academic with head-oscillation issues. Irene appears in one case. (As does Moriarty.) She is mentioned in another. (As is Moriarty.) But both remain iconic figures in the Sherlock Holmes canon, and I would posit that this is the reason: they absolutely defy our expectations of them, and they redefine Holmes’s world in doing so. They make him capable of failure. And in both cases, he respects them for it wholeheartedly.

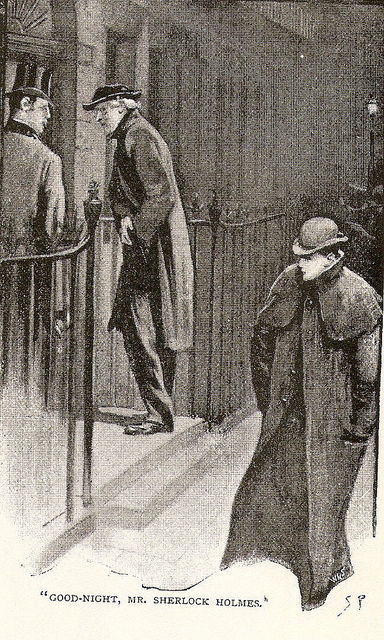

Sherlock Holmes is a ninja and a boxer and a singlestick fighter and a hottie and a genius and an artist, and we adore him, but he needs to be put in his place from time to time. In the very first short story in which Holmes appears, and I cannot emphasize this enough, he gets his ivory ass kicked by a girl wearing trousers. And lest we forget, this story was written by a white dude whose colonialist mores wouldn’t ever have been questioned by any of his peers—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a gentleman and a scholar and a divorce reform advocate, no question. But he was hardly a revolutionary, and he still decided that his chosen protagonist’s first short format case would be a gleeful schooling by a woman in a questionable profession who owns her autonomy, mops the playing field with the King of Bohemia, and ultimately gets the groom and whisks Godfrey Norton off on her muscled white charger.

Why is this good storytelling, and what do we take away from Adler as a result? First, Irene Adler exists fully as a completely separate entity from Holmes and Watson, one who is capable of besting them. When she wins the day, we understand that Holmes gambles from time to time, takes risks and loses his wagers, and this allows narrative tension to exist even though his skills are almost superhuman. If we were to look at Holmes as a statistical bet and think he’s unstoppable, where would be the point in reading the story? Defeating him makes readers crave more dramatic tension, and Doyle was a genius to realize this.

Second, unlike many characters who represent either a Problem to Be Solved or a Victim to Be Saved or a Threat to Be Thwarted, Adler simply has plans that do not coincide with those of the great detective or the good doctor. She isn’t a menace to them and she isn’t a boon either. She’s a person. Adler is simply trying to live her life on her terms and take a hot lawyer to bed when she feels like it, and the greatest thing about this is that Doyle ultimately says AW YISS and lets her get away with…

…were you filling in the blank with murder?

And here is an interesting point: the Irene Adler of the canon is one true Lady Gaga-style free bitch, and she is cast as the antagonist, but she never stoops to any measures other than retaining a photograph which belongs to her, presumably, and…cross-dressing? (Do you have to stoop to cross-dress? You have to stoop to pull trousers on, but…never mind.) It’s interesting that modern adaptations have chosen to make Adler either 1) complicit with the archvillain Moriarty, or 2) ACTUALLY the archvillain Moriarty. Rachel McAdams is fabulously coy but acts nevertheless as his postal service. Lara Pulver is delectably brilliant but hires him to learn how to “play the Holmes brothers.” And Natalie Dormer…well…*cough.* All nods to her strength of character and her feminism. But surely we ought to question why nowadays Irene must be a villain in order to exist in a narrative.

So while we love all of these Irene Adlers for their resourcefulness, their fearlessness, and their charm, let us never forget to raise a glass to the canonical Adventuress as well: the Woman, who proved that you don’t have to be either a villain or a damsel in order to win the day.

Irene Adler is one of the most famous characters in all the Sherlock Holmes canon. She eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex, and every single incarnation of her has been a fascinating delight, even when squirrelly bits worm their way in. And for your wisdom and your love of high adventure, Ms. Adler, we salute you—no less than for your general cheekiness, and your capacity to put even Sherlock Holmes in his place.

Lyndsay Faye is the author of several novels, has been translated into 13 languages, but remains in love with English. You can find out more about them at lyndsayfaye.com & poke her on twitter @LyndsayFaye.

BSB Lyndsay, ASH “The Fascinating Daughter of a California Millionaire,” BSI “Kitty Winter.”

She also works well because we know so much about her and so little. In addition to the above description, she’s from New Jersey (and American and therefore nearly as alien to English men as Hottentots), she’s an accomplished singer, a great beauty and charmer. After that, it’s up to us to fill in the blanks.

It is one of the reasons that I adore Carol Nelson Douglas’s Irene Adler mysteries, where Irene is center stage, as a detective in her own right.