Femme Friday: Lady Mary Brackenstall

Welcome back to Femme Friday, and let us introduce you to one of the most stalwart women in the entire canon: Lady Mary Brackenstall.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was not always a man of progressive ideals: he was anti-suffragist and pro-imperialist, a British gentleman of traditional sensibilities in many ways. That’s one reason why Lady Mary Brackenstall is one of his most intriguing female characters. The story in which she figures—“The Adventure of the Abbey Grange”—is a treatise on the need for divorce law reform, and Lady Mary is a symbol of the ultimate triumph of a victim over her abuser. Basically, she’s a stone-cold badass.

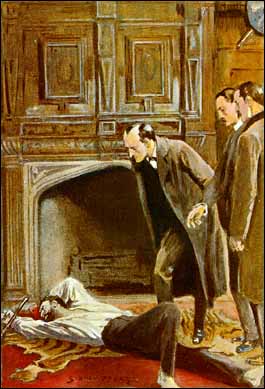

“Abbey Grange” was published in 1904, and follows Holmes and Watson as they attempt to solve the murder of Sir Eustace Brackenstall, who had his head smashed in “like a rotten pumpkin” (there’s some imagery for you) at his home in Kent. The case is nearly over before it begins; by the time Holmes and Watson arrive at Abbey Grange, Brackenstall’s wife, who witnessed the murder, has regained her composure and given a full account which, according to Holmes, “is corroborated by every detail we see before us.” A remarkable statement, considering the whole thing, as Holmes later discovers, is a complete fabrication.

Thus we begin to appreciate Lady Mary: bold enough to lie to Holmes’ face, calm enough to pass off it off without question, and clever enough to convince England’s leading mind that he should trust her words over his observations. (He noticed, after all, the key clue directly, but talked himself out of it because his instincts contradicted Mary’s tale.) Holmes himself later tells Watson that “The lady’s charming personality must not be permitted to warp our judgment.” Wait, was Holmes allowing his judgment to be warped by a GIRL? This must be some woman! How charming is she? The expert in these matters is always Three Continents Watson, so let’s see: “Graceful,” “womanly,” “beautiful,” blonde,” “golden-haired,” blue-eyed,” “perfect complexion,” and let’s not leave out her “quick, observant gaze,” and “alert expression.” Watson doesn’t miss a trick.

The subtext of the story is even more illuminating when it comes to Lady Mary’s character. When we meet her after her husband’s death in early 1897, she has only been in England for 18 months. Originally from Adelaide, Australia, Lady Mary left her home with only her trusted maid in tow, and, as far as we can tell, no immediate prospects awaiting her. It would be fair, therefore, to brand her an adventuress, and, true to form, she attracts men like a bacon-wrapped stripper. She is married to a wealthy baronet within six months, leaving a trail of broken hearts behind her.

None of this is what is most remarkable about Lady Mary, however. Her most remarkable quality is her will to survive in the face of physical, verbal, and deep psychological abuse. Her husband was a drunkard and a villain. Not only did he punch her in the face and stab her with a hatpin (seriously? WTF?), he threw a decanter at her maid, called her “the vilest name that a man could use to a woman” (we can only guess), and poured petroleum on her dog and set it on fire. When all of this comes to light during the investigation, she does not cower and she is not ashamed. Instead, she eloquently declares that “It is a sacrilege, a crime, a villainy to hold that such a marriage is binding. I say that these monstrous laws of [England] will bring a curse upon the land–God will not let such wickedness endure.”

With this, Lady Mary Brackenstall establishes herself as a testament to the perseverance of high spirit and true beauty in the face of injustice. We are given more hope and closure than we often get for the victims of these tales, as the killer—Captain Jack “fine specimen of manhood” Crocker is absolved by Holmes and Watson, and invited to return in a year’s time to make his suit to Lady Mary. We can only infer that this picture of wit and grace has not only survived her ordeal but, to cap her victory, pocketed a sexy sailor who appreciates her for the wickedly fierce woman she is. Rock on, Lady Mary. Rock on.

Ashley D. Polasek holds a PhD in English, with a specialty in adaptations of Sherlock Holmes, a subject on which she has published in Adaptation, Literature/Film Quarterly, Transformative Works and Cultures, Viewfinder, and The Journal of Victorian Culture Online, among others. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and an Honourary Research Fellow at the Centre for Adaptations at De Montfort University.

Ashley is the co-editor, with Lyndsay Faye, of Behind the Canonical Screen (BSI Press, 2016) and the co-editor, with Prof. Deborah Cartmell, of The Blackwell Companion to the Biopic (Wiley-Blackwell, forthcoming 2018). You can follow her on Twitter @SherlockPhD