Baker Street: The First Sherlockian Musical

With Lyndsay Faye’s Dust and Shadow being adapted for the singing stage in the coming months, what better time to take a look at Sherlock Holmes’ history in musical theater? Setting aside the many non-musical or “straight play” adaptations that have amassed since William Gillette first sought permission from Doyle himself, there have been a fair number of musicals devoted to the detective as well. Dust and Shadow comes in at number four.

The other three include Baker Street (1965), Sherlock Holmes: The Musical (1988), and My Dear Watson (2014). Despite Baker Street receiving four Tony nominations and winning one of them for Best Scenic Design, it drastically under performed. As the show’s Wikipedia page puts it:

“Producer Alexander H. Cohen felt the show was such an event that he announced, prior to the opening, men would not be admitted unless they were clad in jackets and ties, and women would be allowed in only if they wore dresses. This policy quickly changed once the mixed reviews were in and Cohen realized he needed all the business he could get, no matter how it was attired.”

After reading Baker Street, I believe that the writing behind this musical has more to do with the lack of success, which gives me hope for Dust and Shadow, given that its writer is the amazing Lyndsay Faye. Here I’ll detail what I believe worked well for Holmes’ first musical and what didn’t, starting with the positives.

First, a quick synopsis. Baker Street is a loose adaptation of “A Scandal in Bohemia” with some Reichenbach action thrown in. Captain Robert Gregg of the Palace Guard comes to our hero looking for help, having the same problem the King of Bohemia had in the original story. Holmes takes the case, and everything proceeds like the original story (albeit with a few songs) up until the part where he breaks into Adler’s house á la reverend disguise. She figures out that it’s him and he’s unable to get the letters. Adler shows up at 221B the next day thinking Holmes has stolen her letters as they’ve disappeared, but it turns out Moriarty is behind it instead. The two of them decide to go after the Napoleon of crime and from there it’s a mystery romp with a bit of Reichenbach that ends with Adler and the Baker Street Irregulars rescuing Holmes and Watson from a ship, some stolen objects being returned, and Moriarty’s gang rounded up with the master himself escaping to America. Holmes and Adler follow him, determined to pursue him and (it’s implied) be together forever.

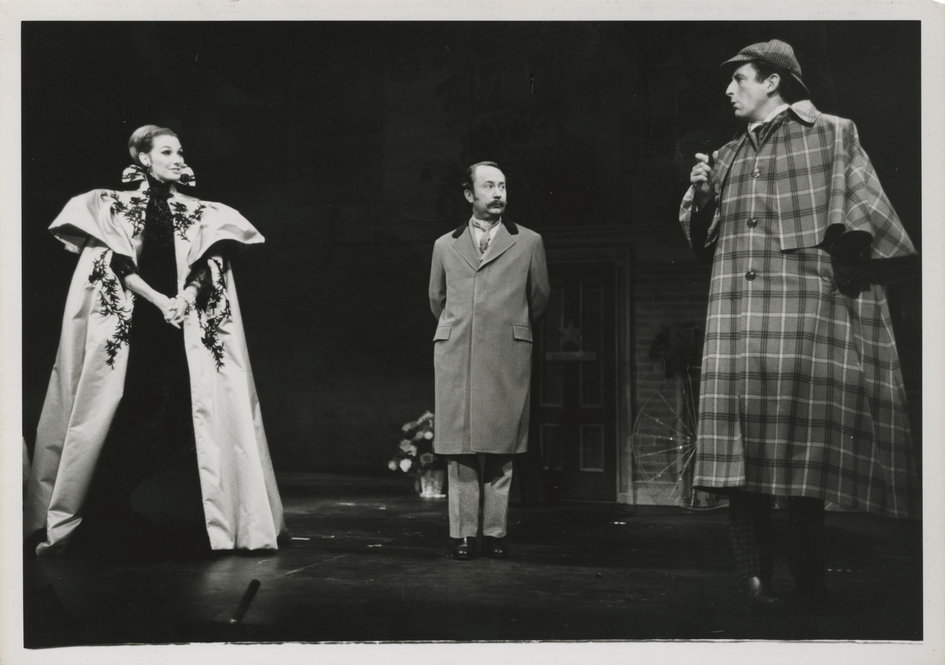

The good stuff is mainly in the beginning. “It’s So Simple” is an awesome song that involves Holmes deducing Captain Gregg and providing insight into his case, which serves to introduce not only the plot but also Holmes’ deductive abilities for those who may be new to the character. Fritz Weaver gives a whimsical performance throughout, and I highly recommend looking it up on YouTube if for no other reason than to hear the way he pronounces the word “nerve” (spoiler alert: it’s hilarious). Right before that was a setup with some action, a canon shout out to The Empty House, and Holmes in disguise. Everything about the first few scenes is solidly done.

From there, however, it took a turn.

Like the canon, there are certain parts of the play that haven’t aged well, such as Adler’s number about shooting Native Americans. She later toasts the downfall of the suffragettes, claiming they “would have us women gain a parcel of rights, and thereby lose a dynasty of privilege.”

What’s more, as much as Adlockers may appreciate an adaptation where their ship becomes canon, they may find their heroine’s motivations unclear. She deviates from her canon counterpart in that she actually does want to blackmail the writer of her letters, but it’s never stated why. What’s even more inexplicable, however, is her sudden 180 regarding the letters. She has an entire five-minute song dedicated to how much she loves them (look up “Letters” too while you’re at it; Inga Swenson shows off the skills that nabbed her a Tony nomination), turned down generous sums of money in order to keep them, locks them in a safe and makes them the first thing she saves when she thinks her house is on fire, and when she believes Holmes has stolen them, she marches right over to 221B with police in tow ready to have him arrested. In the space of a few minutes, however, she suddenly says “I could not care less for those letters” and proceeds to, presumably, drop whatever blackmail scheme she had set up in favor of helping Holmes track down Moriarty and doing whatever he says.

Watsonians may be disappointed too. Watson is reduced to barely more than an extra in this play, with Adler replacing him as Holmes’ partner and the Baker Street Irregulars doing much of the extra casework. You get the sense the writers didn’t much care for him, as he offers to help in the beginning only to have Holmes uncharacteristically turn him down. Aside from getting kidnapped, Watson has a whole lot of nothing to do and is largely forgotten. He does get one short solo at the end where he sings about his late wife (“Married Man”), but unfortunately this doesn’t have the impact it could have. Up to this point, she’s barely been mentioned at all and so it is impossible for us to really feel his grief, and his flirting with every woman he sees throughout the play (including Adler) doesn’t exactly line up with what we might expect of a loyal man like Watson who recently lost a wife he was devoted to.

The mystery is similar to canon, lots of disguises and a journey through London that everyone reading the play will wish they could see live. One cringe-worthy bit was Holmes’ uncharacteristic lack of planning. He and Adler are in search of a man only she has seen and only then for about thirty seconds, they have no idea where he is, and they don’t seem to have a plan in place for when they catch him. Holmes tells Adler that if she sees him, she is to wave her handkerchief above her head in a circle as their signal. Seems a bit…obvious, and it must have been because the villains recognize it right away and act accordingly.

Still, in a musical it’s the songs that are important, and there are a few goodies. Inga Swenson especially has the voice of an angel, and I could sing “It’s So Simple” and “Cold Clear World” all day. When you have Jerome Coopersmith, the man behind Fiddler On the Roof, on your side, you’re bound to get some catchy tunes.

Given the Tony’s for Scenic Design and Costume Design, we can safely assume that those were done expertly, and if the pictures in my book are anything to go by, the choreography was incredible. Though it’s unlikely anyone will ever see it live again, you can read the play and listen to the music. The songs are on YouTube and the CD and book are available on Amazon.

Guest Poster: Devyn is a devoted Holmesian and Watsonian as well as a writer. She has 50+ fanfics to her screen name and is always working on a poem or story. Outside of Holmes and writing, she enjoys reading, video games, and exploring new places.

Want to write for us? We accept guest posts! Find out more information here.